We’ve just updated the text of the King James Version we use in PocketBible. Whether you’re a devoted reader of the KJV or only have it installed because it came bundled with your copy of PocketBible, you should welcome this move to a more pedigreed version of the text.

We’ve just updated the text of the King James Version we use in PocketBible. Whether you’re a devoted reader of the KJV or only have it installed because it came bundled with your copy of PocketBible, you should welcome this move to a more pedigreed version of the text.

Laridian has long been criticized for the perceived lack of attention we’ve paid to our KJV text by those for whom the accuracy of this text is a major issue. The previous version of our text was from an unknown source and contained American spellings and modern replacements for many archaic words. In some cases, these aspects of the text went unnoticed but in others they were very apparent and called into question the quality of the rest of the text.

The most commonly cited problem was our use of the word thoroughly in 2 Timothy 3:17, where the original 1611 KJV uses the archaic word throughly. While it is the case that the word throughly is defined as “thoroughly; completely”, there are some who feel the original word conveys some additional meaning that is lost by the change to thoroughly. This, despite the fact that Vine’s Expository Dictionary says “For THROUGHLY see THOROUGHLY” and even Webster’s 1828 American Dictionary says “For this, thoroughly is now used”. This is just one example, though arguably the most significant, of about 100 spelling changes between our previous edition of the KJV and our newest release.

A Little History

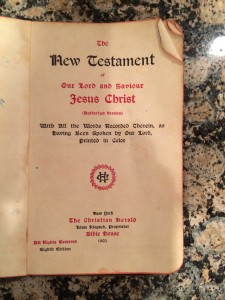

The Authorized or King James Version of the Bible was the result of a project to revise the text of the Bishops’ Bible, which was the Bible of the Church of England at the turn of the 17th century. In 1604, a committee of fifty-four men were appointed to undertake the revision. Work was delayed until 1607, by which time only forty-seven of the original appointees were available to work on the project. The instructions given to the translators were to alter the text of the Bishops’ Bible as little as possible and to use the text of Tyndale, Coverdale, Matthew, Whitchurch, or Geneva when those translations agree more closely with the original Hebrew and Greek texts. The editors worked in several teams, each tackling a portion of the books of the Bible. When the work was complete, representatives of each group oversaw a final editorial pass through the text and two men worked closely with the printer to supervise the first printing in 1611.

A number of factors made it impossible for any two early print runs of the KJV to be identical. First, the printing technology at the time required that a single page be created by laying out individual pieces of type (each representing one letter, punctuation mark, or space) to create a form. Once the entire print run for that page was completed, the type was reclaimed to create the next page. By necessity, then, the second and subsequent printings of the Bible had to be re-set from scratch using the original documents or the previous printing as a guide. While errors in the previous printings could be corrected at this time, the resetting of every page made it possibile for new errors to be introduced. In 1725, printers at Cambridge University came up with the idea of making a plaster mould of an entire form, then using this to cast a metal stereotype or cliché from which identical subsequent prints could be made. This helped reduce the errors from constant resetting of the text.

A second source of variation in the text was the lack of a standard English orthography (spelling). Most people in the 16th and 17th centuries experienced reading vicariously — the actors in Shakespeare’s plays repeated his words on stage, and the clergy read the Bible aloud to the congregation. As long as the words could be pronounced in a way the hearer could understand, the spelling of the word on the page was irrelevant. It would be another 150 years before the idea of “standard” spelling and even the concept of a dictionary of the English language would come about. In the meantime, there might be two or more different spellings of the same word within one printing of the Bible (or any book for that matter).

To complicate this further, and because correct spelling simply wasn’t an issue, typesetters would add or remove letters from words to make them fit better on a line of type. This introduced another opportunity for variation.

Even after stereotyping made it possible for one publisher to maintain consistency between printings of the same book, each publisher created their own forms and thereby introduced their own changes into the text. Publishers also felt free to add or remove footnotes, change punctuation, and revise the spelling or word usage for their particular audience.

The result of all of this is that we have literally hundreds of different versions of the King James Version text on bookshelves around the world, created over a period of more than 400 years by dozens of publishers using a variety of printing techniques. Each of these is labelled “King James Version” and none come with a list of how they differ from the printing before them, let alone the original 1611 text.

The Age of Electronic Publishing

In the late 20th century it became possible for anyone with a high-speed scanner and optical character recognition software to create an electronic copy of the King James Version text — and they did. Our previous King James Version text was the product of one such person’s efforts. We don’t know which of hundreds of available versions of the KJV text they used, but we know it had Americanized spellings (honorable for honourable, razor for rasor, counseller for counsellor, etc) and modern proper names (Jeremiah instead of Jeremy or Jeremias, Noah instead of Noe, Isaiah instead of Esaias, etc.). It also used a number of modern words in place of their archaic counterparts (the previously cited thoroughly in place of throughly, privately in place of privily, food in place of meat, two in place of twain, etc.).

Laridian’s Historic Position

Because the KJV has been around for 400 years; because it lived through every significant improvement in publishing since moveable type; and because we could find no two KJV Bibles (especially from different publishers) which agreed with each other, we took the position that there was no “best” KJV text. In every case cited by a customer, we could find an example of a KJV Bible from a major publisher that agreed with our version and another that agreed with them.

Lacking an obvious answer to the question “Which KJV is the KJV?” short of the 1611 text (which nobody reads since it uses “u” for “v”, “j” for “i”, and something like “f” for “long s”, rendering it virtually unreadable), we turned to two authoritative sources. First was Cambridge University, which is the steward of the Crown’s copyright on the King James Version in the United Kingdom. During a conversation over a meal, I asked if they had electronic files for the “official” King James Version — assuming there was such a thing, perhaps in a vault buried deep under London. Had I not been paying for their dinner, I would’ve been laughed out of the room. They repeated much of what I’ve stated above, and added the fact that every publisher over the years has made their own “corrections” and changes to the text, including Cambridge itself. They could offer me no advice other than to use one of their more recent printings (for which they had no electronic files). Since that would carry no more weight of being “the” KJV than the one we already had, that seemed like a waste of time.

I next turned to Dr. Peter Ruckman, perhaps the most well-known authority on the “KJV Only” position. Dr. Ruckman argues not only that the KJV is the only accurate English Bible in existence, but that it supersedes the original Hebrew and Greek texts in any question over interpretation of the Word of God. According to Dr. Ruckman, translations of the Bible should be made from it, not from Hebrew and Greek. I wrote Dr. Ruckman a letter asking for his recommendations for an “official” text of the King James Version that would satisfy the requirements of his most vocal followers for an accurate text. Dr. Ruckman scrawled “IDIOT” over my letter and sent it back to me, with the comment “any Gideon Bible”. I pulled my Gideon Bible off the shelf and found it to be a modern English version, not the KJV at all. Of course, I don’t believe Ruckman was making the case that the Gideons were the Keepers of the Authoritative King James Version Bible Text, but rather that I could literally grab any KJV Bible off the shelf, even the free Gideon Bible I found in a hotel, and use it in our software.

When the appeal to authority failed, we simply settled into distributing the KJV that we had and left it at that.

The Pure/Standard Cambridge Edition

Once or twice a year we are contacted by PocketBible users who have a serious problem with our KJV (usually citing the use of thoroughly in 2 Tim 3:17) and encouraging us to publish “the” KJV (and threatening us if we don’t). None of these users have ever been able to point to a definitive, authoritative source for this text, but recently we were directed to two sources: The Pure Cambridge Edition (PCE) at www.bibleprotector.com and Brandon Staggs’ Common Cambridge Edition at av1611.com. Both of these sites claim to have done extensive research to produce an electronic edition of the text that matches that in use by Cambridge University Press around 1900-1910, down to the last punctuation mark, capital letter, and use of italics.

We downloaded these texts and compared them to each other. They differ in about a dozen places, none of which are anywhere near as significant as the use of thoroughly for throughly in 2 Tim 3:17. After looking at some other similar sources, we settled on a version of the text that draws mostly from the Pure Cambridge Edition except in a couple places where we felt the Common Cambridge Edition was better. (In particular, we hyphenate Elelohe-Israel and Meribah-Kadesh instead of creating the “camel-case” spellings EleloheIsrael and MeribahKadesh used in the PCE, and we chose to leave out the footers THE END OF THE PROPHETS after Malachi 4:6 and THE END after Revelation 22:21.)

It was fairly trivial to convert this text to PocketBible format. The hard part was merging Strong’s numbers into it, but we’ve done that to create an updated version of our King James Version With Strong’s Numbers product as well. This has the additional benefit of bringing these two texts into agreement with each other, as even our own KJV and KJV/Strong’s texts had disagreed in a number of places.

Lessons Learned

We’ve gained a new appreciation not just for the King James Version in this process, but also for the history of the English language and printing technology. The myriad variations on the KJV text had led us to “give up” and settle for what was easy. However, this project created the desire to produce something of historical validity and significance, even if it can’t be said to be “the” KJV.

While we don’t agree with those who argue that the KJV is the only English Bible we should be reading, we do agree that it has historical significance and that we should provide a version of it that meets with the approval of those who put it on a taller pedestal than we do. We believe this edition of the KJV for PocketBible meets that standard.

We’re considering publishing some earlier editions of the KJV just for their historical value. While we don’t find reading the 1611 text to be particularly edifying, we do find it interesting. For example:

“And as Moses lifted vp the serpent in the wildernesse : euen so must the Sonne of man be lifted vp : That whosoeuer beleeueth in him, should not perish, but haue eternall life. For God so loued yͤ world, that he gaue his only begotten Sonne : that whosoeuer beleeueth in him, should not perish, but haue euerlasting life.”

I’m particularly intrigued by the shorthand rendition of the word “the” in “God so loued yͤ world”. This comes from the Early Middle English spelling of “the”, which was þe (the archaic letter thorn followed by e). When printed in the common black letter or gothic font, thorn looked very similar to y, and printers (especially in France where thorn did not exist in their alphabet) would substitute the letter y. When needed to make the words better fit on a line, the e would be placed above the y as you see here. (Another example is the word thou which was often shortened to yͧ.) It’s easy to imagine how yͤ became “ye” in “Ye Olde Book Shoppe”, and why “Ye” in this context should be pronounced with a “th” sound like “the”.

Anyway, I digress….

You can simply download the KJV from within PocketBible if you’re running PocketBible on a platform that supports that feature, or, if you have PocketBible for Windows Desktop, go to your download account at our site to download a new installation program for the KJV or KJVEC (KJV with Strong’s Numbers).

We don’t talk much about security issues at our website for obvious reasons – any information we provide could inform a hacker and provide them a shortcut to circumventing security on our site. We’ve recently made some changes that we want you to be aware of for a couple of reasons: First, the changes are comprehensive and as a result, could affect you in ways we haven’t anticipated. Second, we want to reassure you that your information is and always has been secure.

We don’t talk much about security issues at our website for obvious reasons – any information we provide could inform a hacker and provide them a shortcut to circumventing security on our site. We’ve recently made some changes that we want you to be aware of for a couple of reasons: First, the changes are comprehensive and as a result, could affect you in ways we haven’t anticipated. Second, we want to reassure you that your information is and always has been secure. The changes we’ve made are fairly comprehensive and as a result it’s possible that you’ll have trouble signing into your account if you have inadvertently been taking advantage of a shortcoming in our previous account security methods.

The changes we’ve made are fairly comprehensive and as a result it’s possible that you’ll have trouble signing into your account if you have inadvertently been taking advantage of a shortcoming in our previous account security methods.

While it may not be evident from the outside, there are certain philosophies, both of Bible study and software design, that strongly influence each of our Bible study apps regardless of platform. While we’re not at a point where we can give a concrete demonstration of

While it may not be evident from the outside, there are certain philosophies, both of Bible study and software design, that strongly influence each of our Bible study apps regardless of platform. While we’re not at a point where we can give a concrete demonstration of