You would think by 2018 we would be well beyond 20th-century thinking about the relative merits of printed vs. digital Bibles. But apparently not. Recently, a PocketBible user sent me this link and suggested I send the author a copy of our PocketBible app.

The author (Trevin Wax, Bible and Reference Publisher at Lifeway Christian Resources) argues that the form in which we experience the Bible (print vs. digital) matters. How the words of Scripture are presented to us says something (or many things) about those words. The question Wax asks is, does a particular format (in this case, print or digital) take away from our experience of reading, comprehending, and internalizing the message of the text?

The conclusion Wax comes to is that one should continue to read and study their printed Bible because what is lost when going from print to screen is simply too great. I want to address those alleged losses from the perspective of one who doesn’t have the author’s vested interest in print publishing and who has been carrying a digital Bible in one form or another for over thirty years and has been exclusively digital for almost as long.

Wax states that a leather-bound Bible with gilded edges and single-column layout “says something about the value” of the words it contains. But remember that the words of the Bible were originally written by hand on common paper or animal skin. The words themselves carried the value, not the medium. It could thus be argued that wrapping the words of Scripture with fancy covers and printing them on expensive paper with handcrafted fonts and gilded edges takes away from the value of the words themselves and places the emphasis on the physical presentation of those words.

The very argument that “presentation matters” makes the case that the form in which the Bible is published adds to the words of Scripture. I’ve long argued that the benefit of an electronic presentation of the Bible is that it removes the text from its fancy wrapper and places it in a position of prominence. A couple years ago I acquired a KJV Bible from about 1908 that was literally falling apart in my hands. There was nothing special about this Bible except that it was the first “red letter” edition of the Bible. After a couple months of sweeping up the crumbs it left behind wherever I placed it, I sent it off to be rebound. I was stunned by the results. Even though I no longer read or study from the KJV as I once did, I wanted to carry this luscious Bible everywhere. I had developed an emotional attachment to the look and feel of this Bible that overwhelmed the fact that the archaic language of the KJV doesn’t speak to me as clearly as some of the newer translations do.

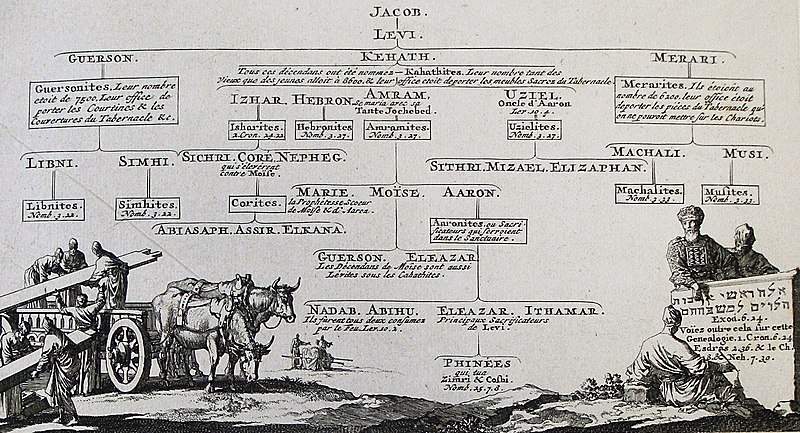

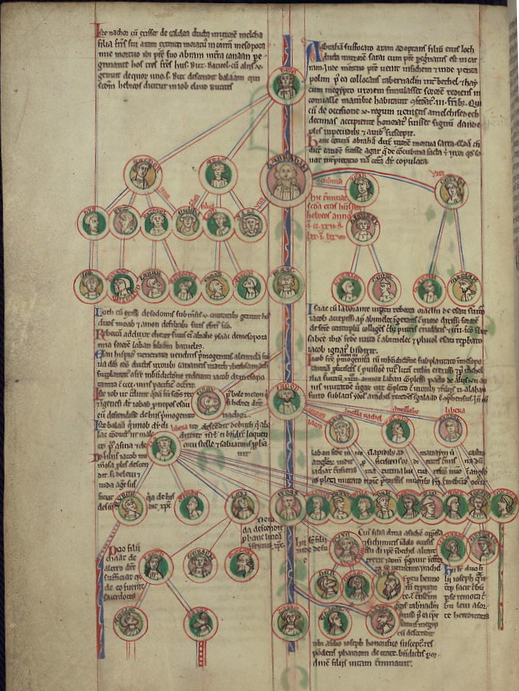

Even binding the books of the Bible together adds meaning and makes implications that some Christians have difficulty overcoming. While I believe the Scriptures were “God-breathed”, it’s a fact that the Bible wasn’t written by one person at one time. It was written by over 40 people over a period of some 4000 years. The copies of those documents that we have were transmitted and copied by hand over centuries. It has only been in very recent history that Christians have had a “Bible” that collects all these works into one convenient binding.

The implications of presenting the sixty-six books of the Bible as one continuous book can include the idea that the worldview, culture, and understanding of God experienced by a person reading an original autograph of the book of Job (considered to be the earliest-written book of the Bible) would be the same as or similar to that of one reading an original account of John’s vision on Patmos as recorded in Revelation (probably the latest-written book of the Bible). We’ve all heard Christians refer to “how they did things in Bible times” – as if the customs of antediluvian nomadic hunter-gatherers were “basically the same” as those of a freed Roman slave living in Corinth when Paul wrote his epistles to the believers in that city. It could be argued that this misunderstanding is exacerbated by our practice of collecting the biblical books of history, law, prophets, poetry, gospels, and epistles all into one book.

But even this “benefit” – that is, that printed Bibles bind the disparate books of the Bible together, presenting a message of unity of message, thought, and ultimate authorship – is not a unique property of printed Bibles. Digital Bibles “bind” the same content together in the same way; they just present it differently.

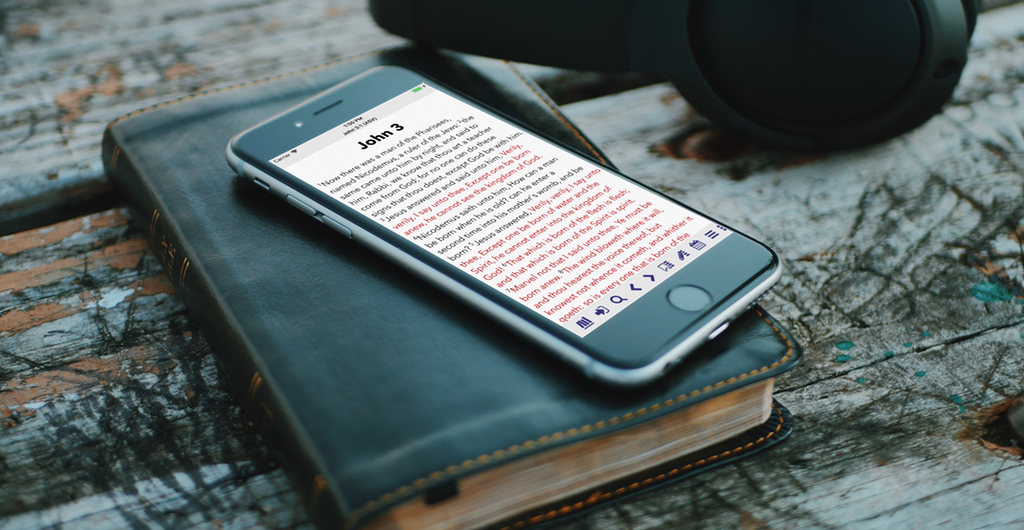

The author cites research that indicates that screens are best for “surface reading” and that books are best for “deep and meditative reading”. I’ve seen those studies. They conclude that reading comprehension is higher when reading books vs. reading text on a screen. But it isn’t clear whether the medium itself is the cause of this difference. Other studies indicated that reading paginated text results in better comprehension than reading scrolling text. For years, our PocketBible app for iPhone presented the Bible in a paginated format for exactly this reason. While many PocketBible users appreciated this format, most objected to it, as it was so different from their customary experience with interacting with text on their device. We could have continued to ignore their pleas for change – arguing that it is for their own good – but in late 2017 we relented and now present text with both scrolling and paginated interfaces.

The point is that the medium (print vs. digital) may not be the cause of the difference in reading comprehension, but rather the way that text is presented in that medium (paginated vs. scrolling). Interestingly, while it’s difficult to change the way text is presented in a printed book, it’s easy to do it with a digital book. In PocketBible, the user can simply choose to interact differently with the text to regain the benefit of pagination vs. scrolling.

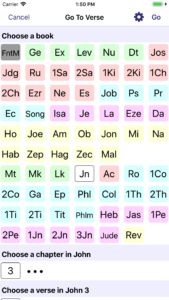

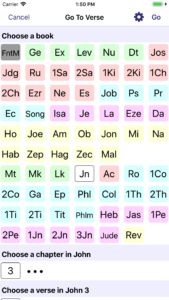

Wax further states that when the Bible is presented digitally, we lose the “geography” of the text – just as we do when using GPS to navigate in an unfamiliar city as compared to using printed maps and our own innate sense of location and direction. Digital Bible readers can simply type “John 3:16” to get to that verse; they don’t have to have a concept of where the Gospel of John lies physically within the text. They may lose the idea that the book of Psalms, which, according to its order, lies right in the middle of the Old Testament, actually lies right in the middle of the entire Bible. They may not realize that the “second half” of the Bible – the New Testament – isn’t “half” the Bible at all — it’s more like one-fourth or even one-fifth of it.

But I would argue that this sense of geography is only “important” because printed Bibles are so difficult to navigate. Small books like Obadiah and Jude are invisible in printed Bibles unless you have a really good idea where to begin looking. But they are just as “big” and “visible” in an electronic Bible as Jonah and Revelation, their larger and more familiar neighbors. In other words, the idea that the geography of the Bible is important is only true if knowledge of that geography is important to accessing the text, which is the important part.

But I would argue that this sense of geography is only “important” because printed Bibles are so difficult to navigate. Small books like Obadiah and Jude are invisible in printed Bibles unless you have a really good idea where to begin looking. But they are just as “big” and “visible” in an electronic Bible as Jonah and Revelation, their larger and more familiar neighbors. In other words, the idea that the geography of the Bible is important is only true if knowledge of that geography is important to accessing the text, which is the important part.

Wax goes on to make a bizarre claim – that we more easily submit to the text when we read it in print than when we read it on the screen, because we have less control over print and are forced to “become more attuned to the complexities of family life, the vicissitudes of social institutions, and the lasting truths of human nature” when reading words on a printed page. This claim is questionable if not outright false just on its face. But if “complexities, vicissitudes, and truths” are what is important, it can be argued that an electronic Bible is better able to convey them because of the depth of resources it places at one’s fingertips.

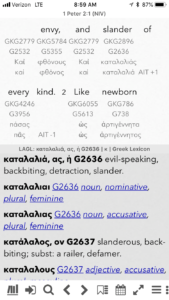

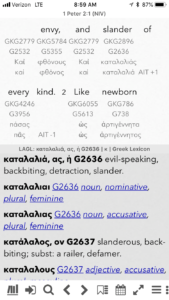

On a recent Sunday, I was listening to a sermon on 1 Peter 2:1-3. Verse 1 tells us to “put aside all slander” (NASB). Having myself been falsely accused of slander (by a sociopath as part of her request for a restraining order against me – but that’s another story), I’m very familiar with the nuances of the term. I was intrigued by the fact that other translations of the same verse used “evil speaking” instead of the very specific term “slander”. I noticed this because my digital Bible, unlike my printed Bible, allows me to simultaneously view multiple English translations, multiple Greek New Testaments, and multiple Greek dictionaries.

On a recent Sunday, I was listening to a sermon on 1 Peter 2:1-3. Verse 1 tells us to “put aside all slander” (NASB). Having myself been falsely accused of slander (by a sociopath as part of her request for a restraining order against me – but that’s another story), I’m very familiar with the nuances of the term. I was intrigued by the fact that other translations of the same verse used “evil speaking” instead of the very specific term “slander”. I noticed this because my digital Bible, unlike my printed Bible, allows me to simultaneously view multiple English translations, multiple Greek New Testaments, and multiple Greek dictionaries.

The word used in 1 Peter 2:1 is καταλαλιας, which literally means “to speak against”. This includes more types of speech than simply slander (making statements about a person that are provably false), including gossip (which is often true statements being told out of context). The proscription of καταλαλιας includes more than slander, a fact I may not have realized if I did not have access to Bibles other than the one most people in my church carry on Sunday.

Wax concludes with an admonition against relying solely on digital Bibles and an encouragement to depend primarily on a printed Bible so as not to lose the benefits of reading the Bible the way God intended it. I believe I’ve shown that the perceived detriments of reading a digital Bible are not negatives as much as they are simply differences between reading words from a screen vs. reading words from a page, and that in some cases, the same positive (or negative) characteristics apply to both screens and pages.

Since we’re making arguable arguments, I’ll make this one. Do a study sometime on occurrences of the phrase “the word of God” or “the word of the Lord” and similar phrases throughout the Bible. (Needless to say, this is easier with a digital Bible.) You will find that the word of God is “received”, “heard”, “given”, and “spoken” but not “written” or “read”. This is not to say that written words are not the Word of God, but rather than there is more to the “word” than its form on a page. The Word of God is the message itself, as communicated to humans by God. It is not constrained to shapes made with ink on pages made of dead trees. It is God’s Word that is “sharper than any two-edged sword”, not your leather-bound Christian Standard Bible. The pages of your printed Bible do not convict of sin or judge the thoughts or intents of your heart, but the Word of God does.

The point is that God’s Word transcends medium, language, and typographical style. The Law was no less authoritative because it was printed on stone instead of paper. Paul’s letters convict believers of sin whether they were the original autographs written on papyrus or parchment, or a modern translation printed on paper or illuminated on a screen. The Spirit of God conveys the Word of God to people through their hearts and minds. Always has. Always will.

Photo byAaron Burden

Out of curiosity, I made a detailed list of all the genealogies, census records, and lists of people I found in the Bible. I found 38 overt genealogies, 53 other lists of (sometimes related) people, and 5 census records (family names and counts). Together, these passages account for 3.5% of the text of the Bible. 3.5% doesn’t sound like much, but it means that in your one-year trip through the Bible, you’ll spend 13 days just reading lists of names.

Out of curiosity, I made a detailed list of all the genealogies, census records, and lists of people I found in the Bible. I found 38 overt genealogies, 53 other lists of (sometimes related) people, and 5 census records (family names and counts). Together, these passages account for 3.5% of the text of the Bible. 3.5% doesn’t sound like much, but it means that in your one-year trip through the Bible, you’ll spend 13 days just reading lists of names.

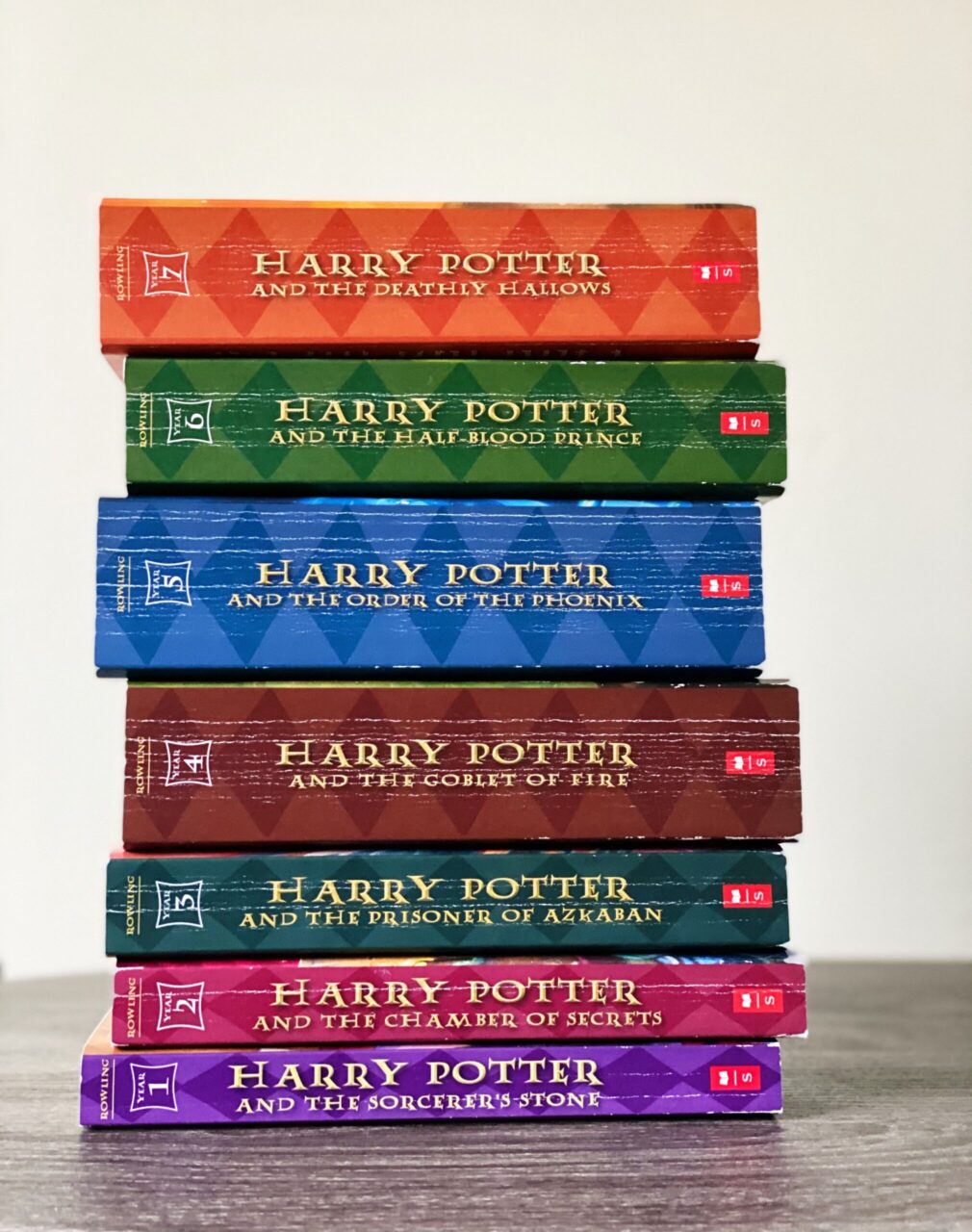

The Bible contains 1189 chapters and a total of 31,102 verses. Those verses combine to contain over 750,000 words. That’s the equivalent of about 11-12 average-length novels. It’s longer than the first 5 Harry Potter books, and you know how much you hate to read those!

The Bible contains 1189 chapters and a total of 31,102 verses. Those verses combine to contain over 750,000 words. That’s the equivalent of about 11-12 average-length novels. It’s longer than the first 5 Harry Potter books, and you know how much you hate to read those!  Imagine adding 8-9 minutes to your morning routine. Most of us would have to get up 10 minutes earlier, and that’s just not going to happen! We could carve it out of the 3 hours per day we spend watching TV, but then how would we keep up with the Kardashians? One website says we spend 63 minutes each day eating. Maybe we could skip breakfast. Or dessert.

Imagine adding 8-9 minutes to your morning routine. Most of us would have to get up 10 minutes earlier, and that’s just not going to happen! We could carve it out of the 3 hours per day we spend watching TV, but then how would we keep up with the Kardashians? One website says we spend 63 minutes each day eating. Maybe we could skip breakfast. Or dessert.

But I would argue that this sense of geography is only “important” because printed Bibles are so difficult to navigate. Small books like Obadiah and Jude are invisible in printed Bibles unless you have a really good idea where to begin looking. But they are just as “big” and “visible” in an electronic Bible as Jonah and Revelation, their larger and more familiar neighbors. In other words, the idea that the geography of the Bible is important is only true if knowledge of that geography is important to accessing the text, which is the important part.

But I would argue that this sense of geography is only “important” because printed Bibles are so difficult to navigate. Small books like Obadiah and Jude are invisible in printed Bibles unless you have a really good idea where to begin looking. But they are just as “big” and “visible” in an electronic Bible as Jonah and Revelation, their larger and more familiar neighbors. In other words, the idea that the geography of the Bible is important is only true if knowledge of that geography is important to accessing the text, which is the important part. On a recent Sunday, I was listening to a sermon on 1 Peter 2:1-3. Verse 1 tells us to “put aside all slander” (NASB). Having myself been falsely accused of slander (by a sociopath as part of her request for a restraining order against me – but that’s another story), I’m very familiar with the nuances of the term. I was intrigued by the fact that other translations of the same verse used “evil speaking” instead of the very specific term “slander”. I noticed this because my digital Bible, unlike my printed Bible, allows me to simultaneously view multiple English translations, multiple Greek New Testaments, and multiple Greek dictionaries.

On a recent Sunday, I was listening to a sermon on 1 Peter 2:1-3. Verse 1 tells us to “put aside all slander” (NASB). Having myself been falsely accused of slander (by a sociopath as part of her request for a restraining order against me – but that’s another story), I’m very familiar with the nuances of the term. I was intrigued by the fact that other translations of the same verse used “evil speaking” instead of the very specific term “slander”. I noticed this because my digital Bible, unlike my printed Bible, allows me to simultaneously view multiple English translations, multiple Greek New Testaments, and multiple Greek dictionaries.