Oil on panel, 65.5 x 82.4 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington DC.

This is the fifth in a series of articles on common excuses for not reading through the Bible.

I’ve spent the last 40+ years studying the Bible, but not necessarily trying to read each word from cover to cover. Several years ago I began setting aside time each day just to read the Bible, with the goal of getting through the whole thing over the course of a year. Having spent many years coming up with excuses not to read the Bible this way, I thought I’d record them here for you. But take note: I’ll be shooting them down in the end, so don’t get your hopes up.

Excuse #5: Why bother reading the entire Bible anyway?

It can be reasonably argued that we only need to read the New Testament.

We meet Jesus in the Gospels. One of the things I like about reading a different translation of the Bible is re-reading the Gospels and re-meeting Jesus. Same characters, same events, but different words so that it sounds fresh and makes you think.

The book of Acts is both an adventure story, as Paul travels thousands of miles on foot to establish churches and preach the gospel, and it is where we first see the teachings of Jesus being put into action by his disciples.

The Epistles address the kinds of issues we face in our churches. Your issues will be different from mine, but they’re all covered.

The Revelation of Jesus Christ to the Apostle John tells us about the future. Well, it does with imagery and symbols, but it does nonetheless.

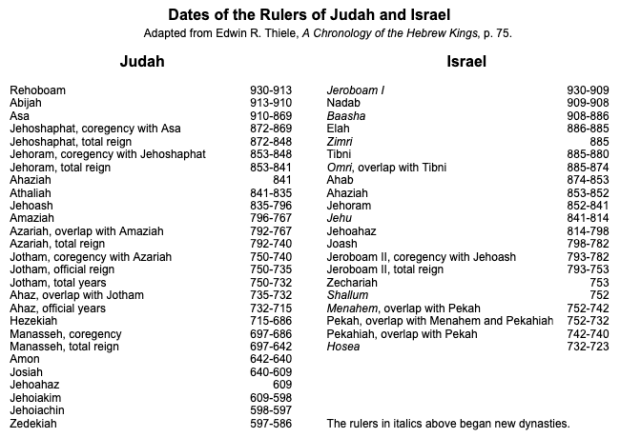

What could possibly be in the Old Testament that would benefit us in any way? I mean, once you have a general idea of what’s there then what’s the point of slogging through it? Creation? Yep; got it. Flood? Know about that. Chosen people? The Jews; heard about ’em. Exodus from Egypt, the Law, the tabernacle, wandering in the wilderness, taking of the promised land, establishment of a king and kingdom, building of a temple, division of the kingdom, good and bad kings, and deportation? Sure, fine, whatever. Return to the land, rebuilding of the temple, promise of a messiah? Yes, yes, I know.

The Familiarity of Home

I was never an athlete, but at 50 years old I started running because my heart was trying to kill me. I started slow. And dumb — the first time I ran a mile, I did it by running straight away from my house, then I had to walk back. It took time for me to figure out that I should run a circular route so I’d end up at home.

Eventually, I ran into parts of my neighborhood that, while just blocks away, were unfamiliar to me. A curious thing began to happen: my concept of “home” was expanding. My “home” went from the yard I mowed every week to an entire neighborhood. My “neighbors” were not just the ones who lived next door to me, whose names I couldn’t remember but whose faces were familiar, but now included a woman a mile away who was always out on her front porch smoking a cigarette. And after you run past the house a few times you happen to see a woman dropping off some kids, and realize the smoking lady is a grandmother who watches her grandkids while mom works.

When we read the entire Bible and not just the few passages our preacher quotes on Sunday morning, our spiritual neighborhood expands. We meet more of our biblical neighbors. We discover Job’s dark sense of humor, not just his suffering. We find that the woman at the well was no unclean Gentile, but, like Jesus, could probably trace her lineage back to Jacob, but through Manasseh and Ephraim. Her debate with Jesus over the correct mountain on which to worship was not the idle babble of some random pagan but accurately stated a religious difference between the remnant of Israel that returned and settled in Shechem, and that of Judah, which settled in Jerusalem.

We also begin to appreciate our own place in history; especially in the history of how God has related to his creation through the ages. Familiar New Testament passages take on new meaning as we see similar thoughts being expressed hundreds of years before. And we’re amazed at the degree to which the Old Testament prophets accurate predicted the events of the New Testament.

Continuity of History

I like to read the Bible chronologically. The more I do this the more I begin to see the entire Bible as one long story. When I start reading Genesis, I will first read John 1:1-5:

1In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. 2The same was in the beginning with God. 3All things were made through him. Without him, nothing was made that has been made. 4In him was life, and the life was the light of men. 5The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness hasn’t overcome it.

It reminds me that this is a book that isn’t just ultimately about Jesus, but it’s literally the story of Jesus. I like to describe the logos or “the Word” or “the Word of God” as God’s message — what God has to say. That message was embodied — took on human flesh — in Jesus. Jesus is the embodiment of what God has to say. In Genesis, God spoke and the universe came into existence — that is, without that spoken message from God, that message that we know as the person “Jesus” — nothing was made that has been made.

God wants to have a relationship with humans; humans rejected God; God punished them and selected one family with which to start over; God tried giving them laws, tried living among them in a tabernacle, tried giving them a king they could see — but none of these things restored that relationship he originally had wanted. So he said he would send a prophet, then the “righteous branch” of David.

All of this happens before we even get to the New Testament. When reading chronologically, you come out of the Old Testament reading Malachi, which is as big of a build-up and as big of a cliff-hanger as you get in the Bible.

“Behold, I send my messenger, and he will prepare the way before me! The Lord, whom you seek, will suddenly come to his temple. Behold, the messenger of the covenant, whom you desire, is coming!”

You come out of the Old Testament knowing that a prophet like Elijah is coming, and you read about John the Baptist. You know how it began in the Garden, how humans messed it up, and you know the only way this is going to every work is if God comes down here and does it himself. And then he does in the next day’s reading. Hollywood couldn’t write this kind of story.

And you wanted to skip the Old Testament — especially the prophets.

Jesus Death Has No Meaning Apart from the Old Testament Law

This is why some people get Jesus all wrong. They haven’t read the Old Testament. They say, “Jesus died as an example.” An example of what, exactly? “Well, Jesus died to show us he loved us.” Couldn’t he have just bought us flowers? How does just dying for some random crime (threatening to destroy the temple, I guess — of which he was innocent) demonstrate ‘love’? “He died for his disciples.” In what way? None of them were being threatened with death — he didn’t die instead of them.

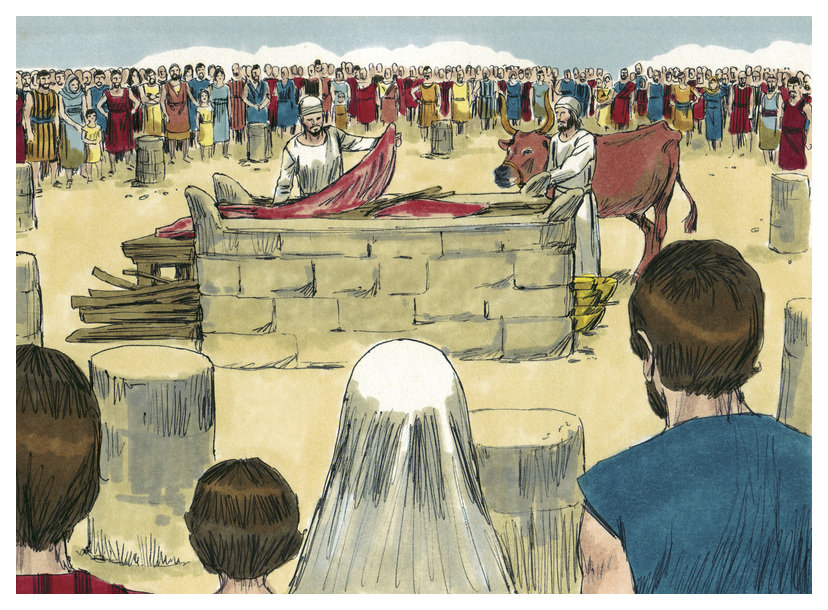

But now insert the Law. Jesus was innocent of his crime, like an unblemished lamb. Jesus died in our place, like that lamb does when it gives its life on the altar to satisfy God’s justice.

At the same time, Jesus’ sacrifice was different. The next day, the Old Testament priest had to sacrifice another lamb, then another the day after that. But Jesus needed to die just once because he perfectly satisfied God’s need for sin to be punished.

The New Testament tells us that Jesus became a high priest after the order of Melchizedek. If you haven’t read the Old Testament, you don’t recognize what the New Testament is talking about. Melchizedek was a priest of Yahweh before Abraham, before Isaac, before Moses, before Aaron, before the Law. (And FYI, he was a contemporary of Job, which you won’t know if you don’t read the Old Testament, and if you did read it, you won’t know it if you read it in Bible order after the book of Esther instead of in chronological order.) He took a tenth of the spoils of Abraham’s battle with Chedorlaomer in the Valley of Siddim before the tenth (or “tithe”) was written into the Law. Jesus isn’t a high priest in the way that Aaron was a high priest; he’s of an entirely different order. An earlier order that wasn’t under the Law.

You won’t know this if you don’t read the Old Testament.

It’s great that you want to read the Bible, and it’s fantastic that you want to read and understand the New Testament. But it’s just one part of the story. And it’s a part that’s going to seem mighty strange if you don’t know what came before it.

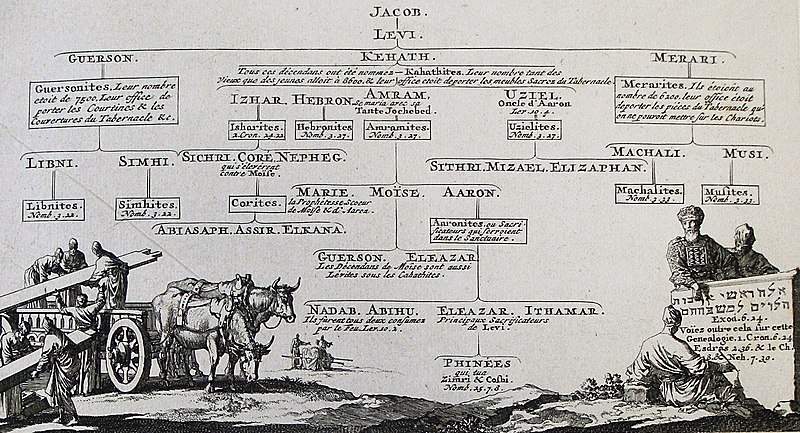

These details are absolutely important — if you’re a descendant of Levi ministering in the tabernacle or temple. But a more general understanding of the Old Testament sacrificial system is all that is needed for Christians trying to read and understand the Bible today. We need to know that God required a blood sacrifice for sin. Then we can understand what we read in Hebrews:

These details are absolutely important — if you’re a descendant of Levi ministering in the tabernacle or temple. But a more general understanding of the Old Testament sacrificial system is all that is needed for Christians trying to read and understand the Bible today. We need to know that God required a blood sacrifice for sin. Then we can understand what we read in Hebrews:

The biblical character Job is among the most ancient persons in the Bible. He is believed to be a contemporary of Abraham (circa 2000 BCE). In the traditional 66-book Bible, the story of Job is found after the book of Esther and before the book of Psalms. The book of Esther describes events in Persia around 480 BCE, around the time that the first remnants of the Jews were returning to Judah after being deported. Most of the Psalms date to the time of King David, 500 years earlier (around 1000 BCE). Based on what you read before and after Job, it would be easy to get the impression that Job was a Jew (he was not), or that he was a contemporary of Saul, David, and Solomon (he was not), or that he lived after the deportation and captivity of Israel and Judah (he did not).

The biblical character Job is among the most ancient persons in the Bible. He is believed to be a contemporary of Abraham (circa 2000 BCE). In the traditional 66-book Bible, the story of Job is found after the book of Esther and before the book of Psalms. The book of Esther describes events in Persia around 480 BCE, around the time that the first remnants of the Jews were returning to Judah after being deported. Most of the Psalms date to the time of King David, 500 years earlier (around 1000 BCE). Based on what you read before and after Job, it would be easy to get the impression that Job was a Jew (he was not), or that he was a contemporary of Saul, David, and Solomon (he was not), or that he lived after the deportation and captivity of Israel and Judah (he did not).

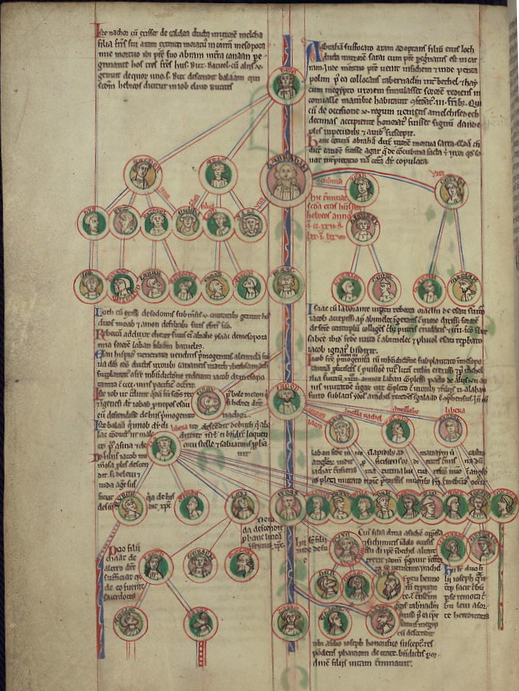

Out of curiosity, I made a detailed list of all the genealogies, census records, and lists of people I found in the Bible. I found 38 overt genealogies, 53 other lists of (sometimes related) people, and 5 census records (family names and counts). Together, these passages account for 3.5% of the text of the Bible. 3.5% doesn’t sound like much, but it means that in your one-year trip through the Bible, you’ll spend 13 days just reading lists of names.

Out of curiosity, I made a detailed list of all the genealogies, census records, and lists of people I found in the Bible. I found 38 overt genealogies, 53 other lists of (sometimes related) people, and 5 census records (family names and counts). Together, these passages account for 3.5% of the text of the Bible. 3.5% doesn’t sound like much, but it means that in your one-year trip through the Bible, you’ll spend 13 days just reading lists of names.

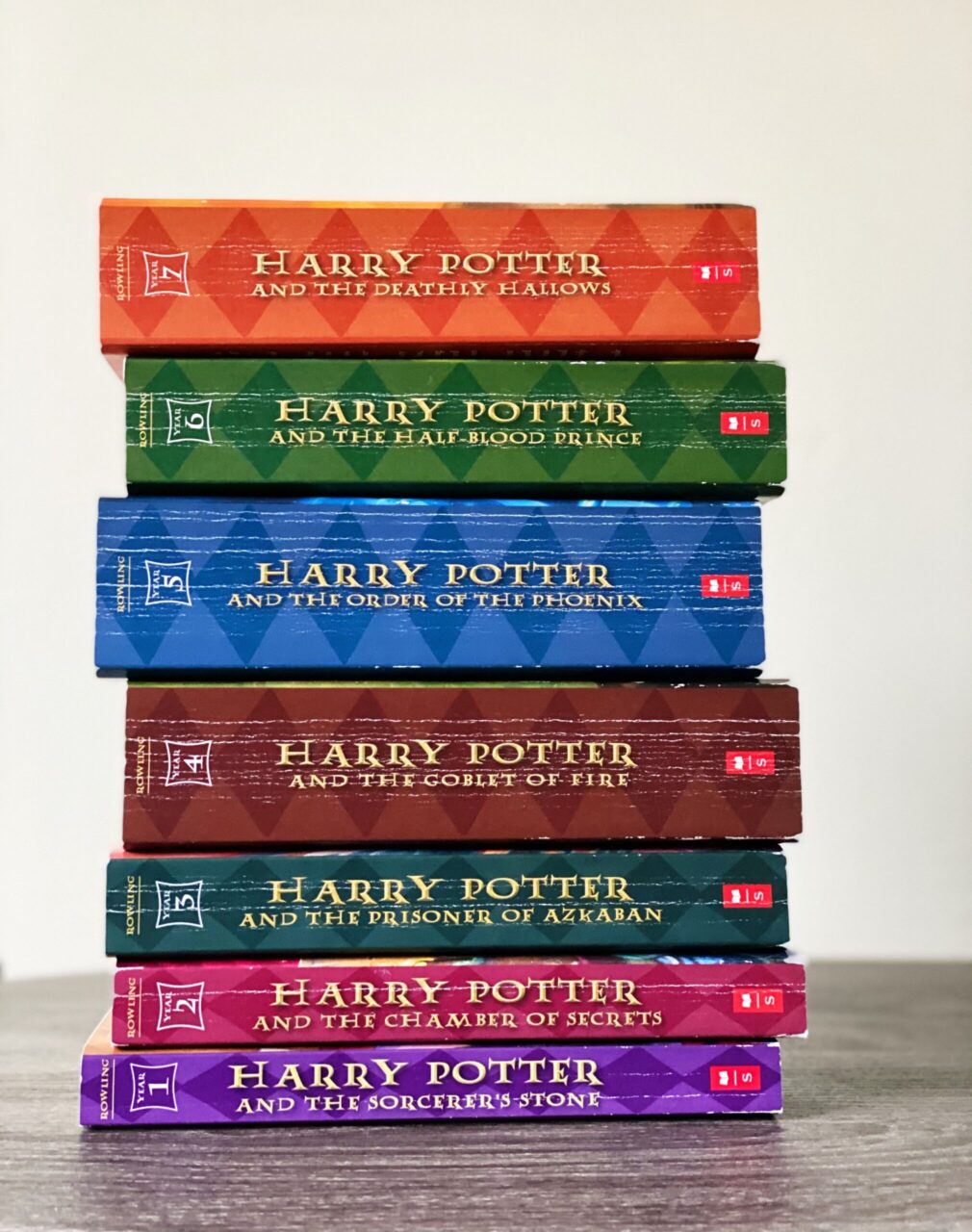

The Bible contains 1189 chapters and a total of 31,102 verses. Those verses combine to contain over 750,000 words. That’s the equivalent of about 11-12 average-length novels. It’s longer than the first 5 Harry Potter books, and you know how much you hate to read those!

The Bible contains 1189 chapters and a total of 31,102 verses. Those verses combine to contain over 750,000 words. That’s the equivalent of about 11-12 average-length novels. It’s longer than the first 5 Harry Potter books, and you know how much you hate to read those!  Imagine adding 8-9 minutes to your morning routine. Most of us would have to get up 10 minutes earlier, and that’s just not going to happen! We could carve it out of the 3 hours per day we spend watching TV, but then how would we keep up with the Kardashians? One website says we spend 63 minutes each day eating. Maybe we could skip breakfast. Or dessert.

Imagine adding 8-9 minutes to your morning routine. Most of us would have to get up 10 minutes earlier, and that’s just not going to happen! We could carve it out of the 3 hours per day we spend watching TV, but then how would we keep up with the Kardashians? One website says we spend 63 minutes each day eating. Maybe we could skip breakfast. Or dessert.